The Part of the Show That's Not Part of the Show [v3]

"The woman I loved died and I'm talking about it onstage at a comedy show and I am bombing."

This is the part of the show that's not part of the show. This is the part of the show where we find out who's on the show”

-Adam Dyck, Edmonton comedian

“Dan and I spent a lovely afternoon out at Elk Island today. It was super windy, but our trail took us through more sheltered areas, luckily. Even managed to see a few birds, despite the wind (some coots, a grebe, and a cormorant, I think). Oh, and a few bison…”

-Dorothy's Facebook status, August 30, 2020

Fall 2022

The woman I loved died and I'm talking about it onstage at a comedy show and I am bombing.

Other than that, things are going okay.

I shouldn't be surprised. Like love, laughter blooms in safety, and Dead Girlfriends are an unsafe topic. Is he making this up? Can he handle this in good taste? Will I be judged if I laugh, or hurt someone else's feelings? The chuckles I'm getting are scattered and uncomfortable, born from awkward tension instead of the smooth release I'm aiming for.

I empathize, and I'm also frustrated. It's not just this group. It's not even just comedy audiences. Everyone seems uncomfortable about death. I understand, but also I’m bereaved over here. Why do I also have to tiptoe around your feelings? You didn't even know this lady, and somehow, when the topic comes up, I feel like I need to comfort you. Instead of finding solace in community, I feel like an exile. I have to restrain from mentioning Dorothy for fear of creating an awkward moment.

The annoying thing is the non-bereaved talk about death all the time, and they do it with shocking casualness. I'm dying over here. I could kill those kids. We pepper our speech with our mortality, a breezy offhandedness painted over deep denial, simultaneously recognizing and repudiating something we know will touch everyone but us and the people we love

No, we're fine talking about death.

Grief is another story.

Grief reminds us that death doesn't just happen. It happens to people.

We aren’t scared of death; we’re scared of feelings. The cracks in a bereaved heart are scary because they're fissures into the abyss. To look into them is to look into oblivion. How shocking is it that we're compelled to avert our eyes?

When someone tells us about a loss, we feel like the expectation is on us to say the right thing. We think they're asking us to make them feel better. We're afraid. We don't want to say or do anything wrong.

I don't need anyone to do anything. I just want the world to know my person existed and what happened to her. I want others invisibly suffering their own losses to know that they aren't alone, that we are brought together by loss, not cast out. That there are others who have shared those moments and–as shocking as it might sound to the uninitiated–that some of those moments are weirdly funny.

And I want to close on laughter and rapturous applause.

Is that so much to ask?

***

I've been in this bar before. The first time was close to three decades ago. I had long hair, a minimum wage job at Pizza Hut, and dreams of rock stardom with the band I'd put together with my next door neighbor and my childhood best friend. Now called River City Revival House, the bar is a basement venue in downtown Edmonton, about ten blocks from the hospice where Dorothy will spend the last weeks of her life thirty years later.

Back then it was called the Bronx, and it was Edmonton's coolest live music venue.

That isn’t saying much, I suppose, but if you live here, it’s something. Nirvana played this bar before they were famous; a framed picture of the original flyer is on the wall. The venue itself has been through a number of iterations since, and though I've been here numerous times over the decades with bands and burlesque shows, the latest renovations have made it a stranger. The stage is on the wrong side of the room: the bar has been moved; the maze-like backstage area that served as a changing area is no longer accessible. If not for the Nirvana flyer from that long-ago show framed on the wall, I wouldn't know it was the same bar.

This is a new place, and I am a new person. Time and change have separated me and this place from our mutual past; whatever history we shared was shared by strangers.

There are people here. All but seven are staff members or comics, and of those seven, two are sitting at the bar having a distractingly loud conversation about mutual funds. That leaves five souls watching, too few and seated too far apart to coalesce into anything resembling a crowd. They're doing their damndest though, and for that I'm grateful.

I can't see them now. The stage lights are too bright for my middle-aged night vision. Instead I listen, delivering words into the dark and hearing silence come back at me threaded with the whir of a point-of-sale machine printing receipts, mutual fund talk from the back of the room, and the occasional nervous laugh or forced chuckle.

I'm aware of a larger mass of people off to my left. These are the other comedians and they outnumber everyone else by close to a three to one margin. Tonight they are still mostly strangers to me, but within the next six months I will know their quirks better than my own. Some sit talking in small groups; some hunch over their notebooks; some drift in and out of the room to vape. A few are watching me bomb– I can hear them occasionally laughing into the space where the audience doesn't. I can’t tell whether they're entertained by the joke or by the joke's failure; my ears haven't developed the precision to determine if the laugh is falling after the punchline or into the uncomfortable silence that follows.

At 49, I am by far the oldest person in the room.

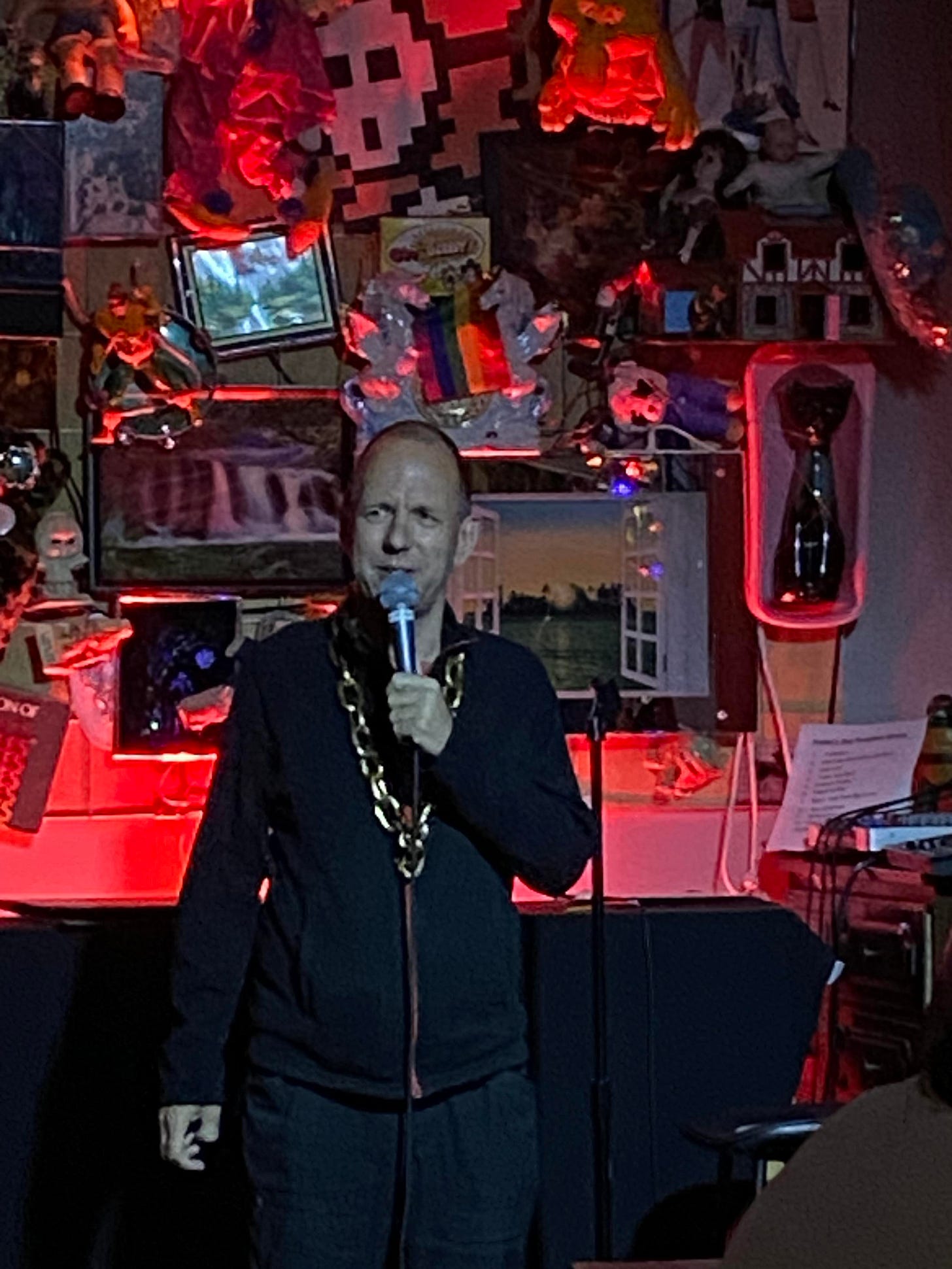

In the silence between jokes, I find myself wondering what the audience sees when they look at me. I'm usually too busy onstage to engage in self-reflection, but I'm told readers like to know what their protagonist looks like. I need a reason to shoehorn my physical description into the story and lying about my thought process seems as artful an excuse as any.

The Comic Strip, the A-list comedy club in town, has mirrored pillars you can see from stage. If you were me looking into those mirrors you would see a middle aged man in a black zip up sweater and black hiking pants bunched at the ankles swaying his weight awkwardly between feet and gesturing with the stiff, uncoordinated self-consciousness of a brain and body who have only recently met and are not entirely comfortable with one another.

If you were you looking at my face you might remark on the blue of my eyes or enjoy how the deep lines beside them give me a wise and gentle look, but since you are me, your attention will focus instead on their slight misalignment, one higher and larger than the other. No glasses yet, but they'll be there by Fall 2023, smudged monofocals, the best I can afford on my health plan. You'll see a man with teeth too big for his mouth, crooked and chipped and crammed together like headstones in a flooded cemetery. You'd see a carelessly shaven face like a badly mowed lawn, and you'd see thinning hair that I shave tight to my skull twice a year and then ignore until it reaches an inconvenient length, poofing around my head like the halo in an eleventh-century painting of a particularly down-on-his-luck saint, or the mane of a threadbare jungle cat (“My lion,” Dorothy called me during the pandemic running her fingers through unruly wing-like tufts at my temple).

In short, you'd see a body built for comedy.

God gave me a gift. I'm a generational genetic marvel bred to be the perfect put-upon pratfall machine. My twitching face and ungainly body language naturally attracts that alchemical blend of empathy and superiority that leaves people laughing at me…whether anyone involved wants it to happen or not.

But when it comes to Dorothy, all these advantages are working against me. I am funny the way a toddler is funny. The Darnedest Things I say, my funny walk, and the surprised look on my face when I fall on my butt is hilarious; the thought of me coming to genuine harm is heartbreaking. Don't get me wrong–there's hilarity in the horrible…but only when the person they're happening to has done something to deserve it.

I didn't deserve to have this happen.

Dorothy didn't deserve to die, and her loved ones didn't deserve to lose her.

But that doesn't mean there's nothing funny anywhere. Laughter can hurt and laughter can hide, but laughter can also point towards truth. Deserved or not, we live in death’s presence, which means it connects us. We might die alone, but we experience death as a community, even if its taboo nature makes it something we struggle to talk about openly. And the shared unspoken is where comedy does some of its best work.

Too bad I'm not the best comedian.

***

I'm not awful.

Or at least, I wasn't.

At the height of my comedy powers I was on the above-average side of okay, what professional wrestlers refer to as ‘a good hand’--serviceable on the undercard, but not someone to build a promotion around.

Tonight I am far from my peak. I tell myself I'm more mature with a deeper well of maturity and life experience to draw upon, but I’m also older, slower of mind, and shaking off over nine years of stage rust. Is it a surprise I'm struggling?

Local comedy has changed in the decade I've been away. There are more shows; when I started in late 2004, beginning comics were lucky to get onstage once a month. Now there are multiple shows a night. There are fewer gatekeepers and more comedy and comedy instruction available. As a result, not only are comics getting better faster, they're doing so on their own terms.

The money still sucks though.

So that's constant, at least. The prospect of sustained financial stability in stand-up–bad to begin with–has gotten worse, though I suppose getting worse is also a form of change.

I'm not here for the money. I can be satisfied in comedy without it being my career. I'm not looking to make a living at it, even as my heart aches for those who are.

I left comedy because I felt I’d reached my professional and creative plateau. Now I'm back, and nobody knows who I am. I'm an outsider in a place that used to be home

It's refreshing.

There's freedom in being a beginner again. I'm free of self- or other -imposed expectations. I can explore and experiment. I can do what I want. I'm uncovering new and undiscovered layers as I push myself to find ways to do things differently than before. Each night is a revelation. I play with comedy in all its colors, and if the product of this wider palette is bombing in fifty new shades…who cares?

Best of all, comedy fills time. Writing jokes takes time. Going to shows takes time. Editing and reviewing recordings takes time. Five minutes on stage costs hours.

it's good.

I have a lot of empty, silent time. Far better to fill it than to pass the days in my basment suite. It's tiny, but these days it feels enormous, far too big for my life. The walls are too high and far apart. The minutes and hours between getting up and going back to bed melt into a timeless crawl.

Comedy gives me something to do at home and a reason to leave it. The other comics aren't unfriendly, but they aren't overly welcoming either and that's fine. It's social contact without social obligation and that's pretty much all I can handle.

I write. I rehearse. I review.

I show up for every open mic. I enter draw spots, milling shoulder to shoulder with other comedy hopefuls as I write my name on hand-torn scraps of paper from a bartop receipt printer, dropping it into an empty water pitcher or pint glass, and hoping for the best.

“It's all in the fold,” Harshaun Gill tells me, a gangly, two-months-in comedy veteran passing on wisdom, as he contorts his slip of paper in a series of elaborate creases.

I nod, thinking, I bet Ryan Short told him that. Nobody knows me so I occasionally hear second hand stories from a past that I was actually there for. It makes me feel like my own grandpaw.

I manage to get onstage a couple times a week.

Comedy is a spiral. I'm constantly coming around to the same place, a rickety hole-in-the-wall joint I like to call Right Back Where I Started. But looking closer, it's not exactly identical. It's the same view, but from a slightly different perspective. On good days, that perspective feels a little higher. Not every day is a good one.

I've heard grief is also a circular process, but I don't care about that. I went to exactly one grief group session, and I left ten minutes early so I could make it to the Underdog on time for the draw. Comedy was more helpful, I decided. The last thing I needed was to be around depressed people.

I read a book on bereavement that said after experiencing loss, most people slip back into their lives. Contrary to popular belief, those who struggle long term are an exception.

I guess I'm part of the lucky majority.

Comedy isn't therapy. I am not one of those wounded comics looking for healing in all the wrong places. That's a stereotype, one that no longer applies if it was ever true in the first place. This new generation of comedians is well versed in the difference between comedy and therapy, especially since so many are doing both.

Good for them. Personally, I'm mistrustful, not of therapy, but of therapists. I read all the books, but stay out of the waiting rooms.

Comedy is one world. Grief is another. I talk about death and grief onstage, because having been through it, I have something to say Maybe that something will help someone else. But I don't do it for me. I've had plenty of time to process my loss.

She died a full four months ago.

I'm fine.

Like I said, I've read all of the books.

***

I'm here, and I'm bombing

I shouldn't have done this material.

But what choice do I have? There’s always a reason not to tell these jokes. It’s too early on the show. The crowd is too young. They don’t know me well enough.

I want to build something in Dorothy's memory, something not born from loss and sadness, but from love. She is gone but my love flows on. It's dark in here, but in my brain I'm working under the sun, quietly lifting stones into place, shaded by trees while birds sing from the branches, except the birds are these five people and my forest clearing is a downtown bar and my stones are made from dick jokes.

This is a story about comedy. It might also be about grief and loss.

It isn't about how to do those things. I can't teach you comedy or how to grieve. I'm not great at them myself. If you asked for advice, I'd give the same stock reply: there is no right way.

Then again, I'd have to say that, wouldn't I?

Any other answer would be gauche.

Most of all this is supposed to be a love story. Which circles us back to where we started. How do you define love? Is it a feeling? A force? A choice? A moment between two human beings or the sum of those moments through time? I'm not entirely sure, but i do know that love is something you can get BETTER at. You can build your capacity to recognize it, to hold it, to act with it in your heart

Somewhere along the line Dorothy and I became a we. But I'm a me again, and now that I'm just me, I wonder how much of our story I can tell. Her inner life was and remains a mystery. There were ways in which I knew her better than she knew herself and ways i

n which I didn't know her at all, leaving a big Dorothy-shaped hole in this story. ‘We’ has become ‘I’, and we do not like it. A one-person love story isn't a love story. It's a fantasy.

But the feeling of we-ness persists. I am still part of a we, not married, but forever we-d, even if mine is the only perspective I can reliably share. This is a bigger we than the two of us. It's a we that connects me to…well, everything. The we that was me and Dorothy is tethered to something vast and unbound. We're drops in time and space finding themselves back in a limitless ocean that connects us not just to each other, but to a past, present, and future that contains everything and everyone.

I know more about love now than I ever thought possible. The universe has told me a secret. I want to share it, and I hate that I can't explain it.

I’m not a great comedian. I might not even be a good comedian–not to the extent you can measure these things. But I have something to say and I can't quit until it's been said to the best of my limited ability.

I'm off to a rough start.

I shouldn't be surprised. In comedy, failure is both inevitable and public. The only path to success is to show up and keep showing up, allowing persona and material to evolve based on audience feedback. Bombing is a necessary if messy part of the process.

It’s embarrassing that failure has to happen in public. But that's how comedy works. In order to honor Dorothy’s memory I need to fall short many times, and I need to do it in front of people, grinding away in the stand up comedy salt mines,

one five-minute set at a time, on small shows with smaller crowds.

It hurts to make the crowd sad and uncomfortable. It's the opposite of my intention. I know love and I want to share it.

Instead, I'm making folks feel bad.

It's hard to tell what isn't working. Comedy‘s binary feedback system of laugh or no-laugh is outstanding for measuring results but hopelessly inadequate for diagnostics.

Is it my delivery? Is it the set-up? Is it me, personally?

Am I not good enough at comedy or am I just not good enough? You know, as a human.

Comedy brought me back to a sort of life, and I'm publicly murdering it. My dick jokes are wilting like flowers at Dorothy's bedside. Love by itself is insufficient; it needs to be given shape, through skill, good judgement, and experience.

I don't have those things yet, and the audience sees it. They don't hate me; they feel bad for me, and somehow that's worse.

Showrunner Noah Brodeur flashes the light on his phone. Larger clubs will have a designated light, but on smaller shows, phones send the same message: You’ve got a minute left, so wrap it up. I finish my set (“Thanks, everyone. Sorry.”) and leave. There's applause behind me. To my ears it sounds like pity.

“That was really beautiful, man,

” Liam Connell tells me. “Great job,”

Another comic fist bumps me as I pass. “Nice set,” he says, but then agaon, he would have to.

Anything else would be inappropriate.

Barely able to make eye contact, I thank Noah for the spot, apologize for bombing, and slink off to the bus stop.

Hey, remember all that stuff I said earlier? About love and comedy and perspective and bla bla bla?

Fuck all that.

I have failed myself and I’ve failed my love. My phone is heavy in my pocket, a reminder that I recorded this set. I won't listen to it; it will only remind me of my shame. My creative pilgrimage is a fool’s side quest. I'm too old and too untalented to translate love to laughs. I'm lying to myself and I'm dishonoring Dorothy’s memory. This was a terrible idea, and I’m a bad person for even trying.

I’ll never do comedy again.

24 hours later, I’m back onstage.